Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is immigration good for a country, or bad? This question always strikes me as unhelpful. It depends on the country. Even if we couch the question strictly in economic terms, things vary. Immigration adds millions to the coffers of some nations, but has a more ambiguous if not negative impact on others.

To take some more specific examples: the rise of gun violence in Sweden, attributed by the police to gangs led by second-generation immigrants, is bad. Whereas the fact that immigrants and their children are consistently over-represented among founders of successful businesses is good. The Covid-19 vaccines, not to mention the technology underpinning them, were the fruits of immigration.

But a striking pattern emerges when you look at where these different impacts are clustered: almost everything looks better in Anglophone countries. Immigrants and their offspring in the UK, US and so on tend to be more skilled, have better jobs and often out-earn the native-born, while those in continental Europe fare worse. In terms of the fiscal impact, immigrants pay more in than they get out in the US, UK, Australia and Ireland, but are net recipients in Belgium, France, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Language and geography undoubtedly play a role. Anglophone countries benefit from drawing on a huge global pool of educated English-speakers, and from having fewer land borders, allowing more control over who enters the country. But outcomes for immigrants and for the society in which they settle are not simply dependent on language and skills on arrival. Some countries do a much better job of creating environments for people of different backgrounds to integrate into the economy and wider society.

Education policy expert Sam Freedman points out that, in Britain, second-generation children from the poorest Bangladeshi communities achieve better results at school than the average white British pupil, while Black Britons are more likely to attend university than their white counterparts. In the US, Black high school graduates are now as likely to enrol on a four-year college programme as their white counterparts. In France, by contrast, students of North African origin remain much less likely to progress in education.

Even more striking is how things have changed over the generations. The children of immigrants in the UK, US and Canada all experienced smaller racial wage deficits than their parents, but most second-generation immigrants in France and Germany went backwards. Similarly, the poverty rate among immigrants has fallen over the last decade in the UK, US, Australia and Canada, but risen in France, Sweden and the Netherlands.

This stark divergence can be linked to failed integration policies across much of Europe. In France, decades of social exclusion and hostile policing have created entrenched inequalities. In Sweden, one policy placed all immigrants on benefits by default, while housing policy fostered segregation. Today, Swedish immigrants have three times the unemployment rate of the native-born, the widest disparity of any developed country.

Studies show this lack of progress between generations is especially harmful. First-generation immigrants are less involved in crime than native-born citizens. But, in her book Unwanted: Muslim Immigrants, Dignity and Drug Dealing, German ethnographer Sandra Bucerius describes how, while second-generation immigrants in the US and Canada continued to have lower crime levels than the native-born, in Germany crime rocketed among the second generation.

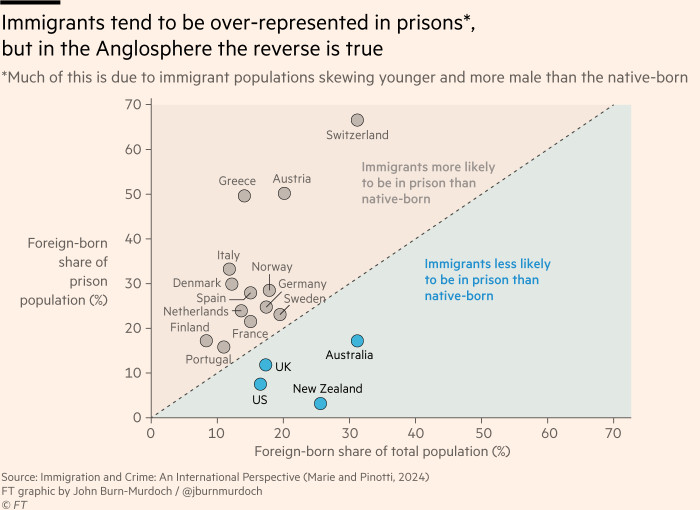

International comparisons find that people with immigrant backgrounds are generally imprisoned at similar or higher rates to the native-born, except in the US, UK, New Zealand and Australia where they are under-represented in the prison population, a sign of successful integration.

On everything from education to employment, earnings to crime, the Anglosphere seems to have figured out how to make immigration work at least reasonably well. This is reflected in public opinion: continental Europeans are more likely to say immigration has been bad for their country, according to figures from Focaldata.

To be clear, the continuing, unedifying debates around immigration to the UK and US demonstrate that, even where successful, it remains contentious. The tangible evidence may indicate benefits; much of the public remains unconvinced. But in a world where countries increasingly compete for skilled migrants to provide demographic and economic boosts, the Anglosphere appears well placed.