Receive free US interest rates updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest US interest rates news every morning.

The US Federal Reserve will defy investors’ expectations and raise interest rates by at least another quarter-point, according to a majority of leading academic economists polled by the Financial Times.

More than 40 per cent of those surveyed said they expected the Fed to raise rates twice or more from the current benchmark level of 5.25-5.5 per cent, a 22-year high.

This is in sharp contrast to the mood in financial markets, where traders in federal funds futures believe the US central bank’s policy settings are restrictive enough to get inflation under control and so it can keep rates on hold well into 2024.

The survey, conducted in partnership with the Kent A Clark Center for Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, suggests that fully rooting out price pressures and getting inflation back down to 2 per cent will require more prohibitive borrowing costs than market participants currently anticipate.

“Some of the signals that we’re getting are that policy isn’t that tight,” said Julie Smith, a professor of economics at Lafayette College, noting that interest-rate sensitive sectors such as the housing market remained “surprisingly strong” despite having taken an earlier hit.

“It doesn’t seem like there is enough pullback from consumers to slow the economy, and I think that’s really the issue.”

Of the 40 respondents polled between September 13 and September 15, about 90 per cent believe the Fed has more work to do.

Nearly half of the economists surveyed forecast the fed funds rate would peak at 5.5-5.75 per cent, indicating one more quarter-point rate rise.

Another 35 per cent expect the Fed to move two more quarter-point notches, pushing the benchmark rate to 5.75-6 per cent.

A small cohort — 8 per cent — think the policy rate will top 6 per cent.

Once rates peak, the economists surveyed were overwhelmingly of the view that the Fed would keep them there for quite some time. About 60 per cent of those polled thought the first cut would come in the third quarter of next year or later.

That is nearly double the proportion of economists who predicted that timescale in June, the last time they were polled.

The survey comes just days before Fed officials are due to meet for their next policy meeting, at which they are expected to again hold off on further action.

The rapid policy tightening since March 2022 has been the most aggressive effort to reduce demand in decades.

While inflationary pressures have receded and the labour market is softening, many of the surveyed economists worry that underlying momentum in the world’s largest economy is still too strong and that inflation will become harder to root out.

Gordon Hanson, a professor at Harvard Kennedy School, said: “Just like there was concern that the Fed was too slow to react, you don’t want the Fed to be too quick to relax.”

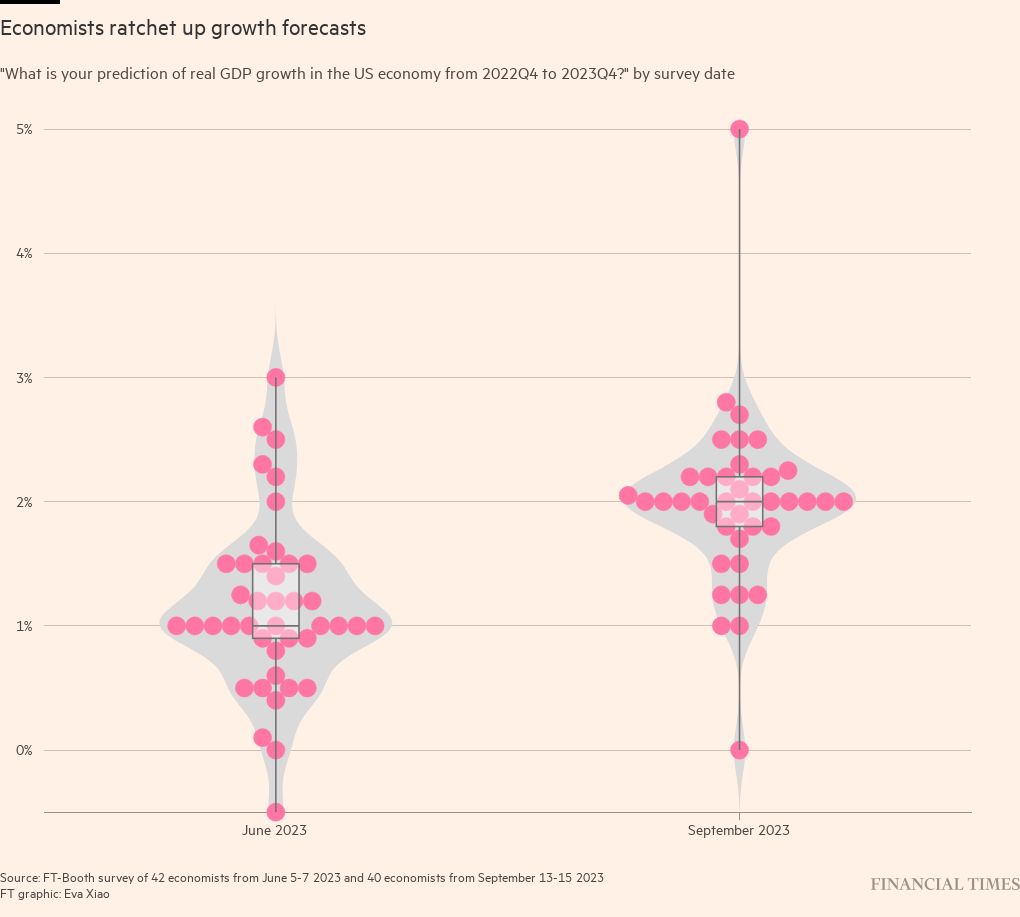

Since June the survey’s respondents have doubled their forecasts for economic growth by year-end, to a median estimate of 2 per cent.

The unemployment rate is projected to settle at 4 per cent, while the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge — the personal consumption expenditures price index once food and energy prices are stripped out — is expected to moderate to 3.8 per cent. It is running at 4.2 per cent as of the latest data in July.

By the end of 2024, only a third deemed it “very” or “somewhat” unlikely that core inflation would exceed 3 per cent. The vast majority saw either even odds or more that it would.

A curtailment of oil supply is the biggest risk to the inflation outlook, they said.

Christiane Baumeister, a professor at the University of Notre-Dame, is among those to worry about energy prices after the decision by Saudi Arabia and Russia to cut supply. She expects prices to rise further, potentially bidding up expectations of future inflation as well as delaying the descent in core price growth if companies opt to pass on higher costs to consumers.

The sharp slowdown in China’s economy could offset this; it is set to drag down global growth in the coming months.

Domestic headwinds, including the reprisal of student loan payments and the looming threat of a government shutdown, could further weigh on demand.

Sebnem Kalemli-Özcan, an economist at the University of Maryland and a member of the New York Fed’s economic advisory panel, is among the majority of economists polled who believe the so-called neutral rate of interest — a level that neither stimulates nor suppresses growth — is higher than in the past for the time being.

This will further delay how quickly the Fed will be able to cut its policy rate next year, she said.

“Even though we have a sense it is higher, we don’t know exactly how high R-star is right now,” she said.

The economists surveyed have become more optimistic about the odds of a soft landing, whereby the Fed can bring inflation down without excessive job losses.

More than 40 per cent deemed it “somewhat” likely that bringing inflation back down towards 2 per cent could be achieved without the unemployment rate having exceeded 5 per cent. Another quarter of the respondents said it was “about as likely as not”.

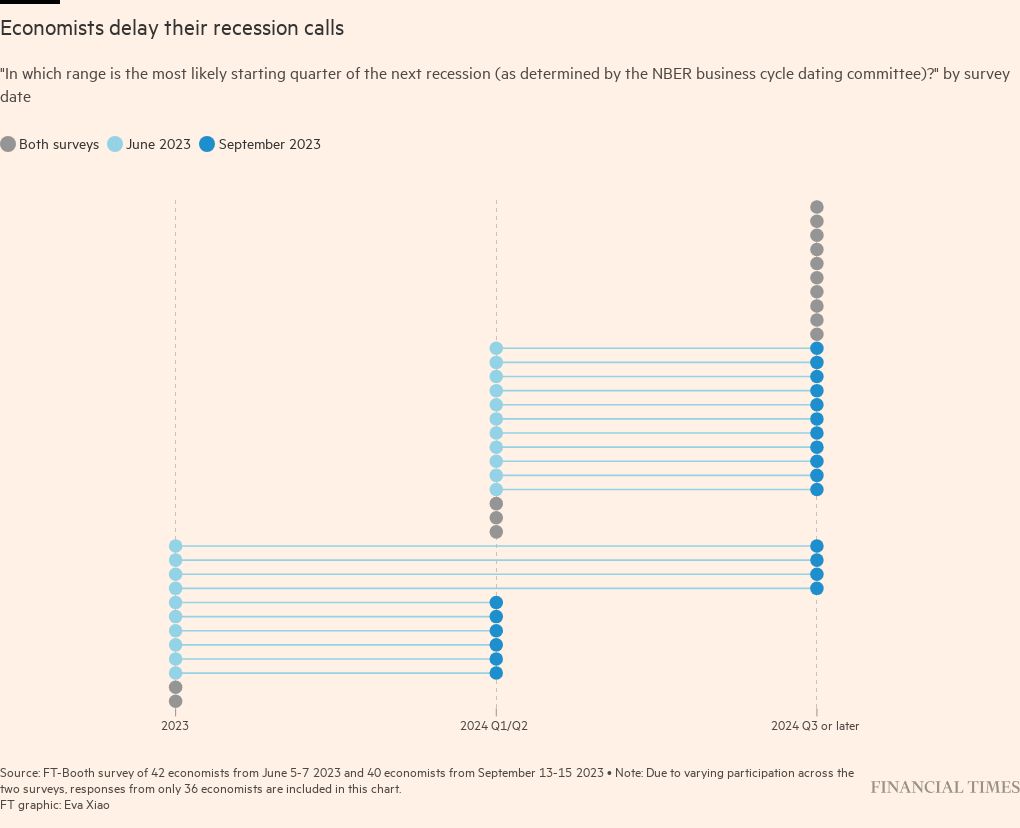

When asked about the timing of the next recession, many pushed back their estimates further than they had previously predicted.