Inflated shipping costs are enabling Russian companies to earn far more from crude oil sales to India than previously recognised, according to a Financial Times analysis which suggests that the charges may have raised more than $1bn in a single quarter.

Russia has, until recently, appeared to comply on this route with western measures designed to curb its revenues which were introduced after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year. Its oil producers have been selling crude to India for below the $60-per-barrel price cap.

But when freight costs are included, they and the traders with whom they work have charged much higher sums.

An FT analysis of ships running directly from Russia’s Baltic ports to India suggests that this overcharging, combined with fees earned from shipping the oil on Russia-linked vessels, may have been worth $1.2bn in the three months to July.

Benjamin Hilgenstock, an academic at the Kyiv School of Economics, which has been studying evasion of the price cap, said: “Inflated shipping costs are a major concern as they effectively create a leak in the price cap regime through which someone, somewhere can siphon off billions of dollars.”

James Cleverly, the UK’s foreign secretary, said: “It comes as no surprise that Putin is becoming increasingly desperate and dishonest in his attempts to mitigate the price cap’s impact — something that has been severely restricting Russian revenues since its introduction. Those aiding Russia’s attempts to fund this illegal war should know, the UK will continue to act alongside our partners to enforce this measure.”

The price cap imposed by the G7 is intended to keep Russian oil flowing while squeezing revenues that could be used to fund the war. But the cap — which places requirements on buyers, shipowners and insurers from participating countries — does not impose any limit on freight costs.

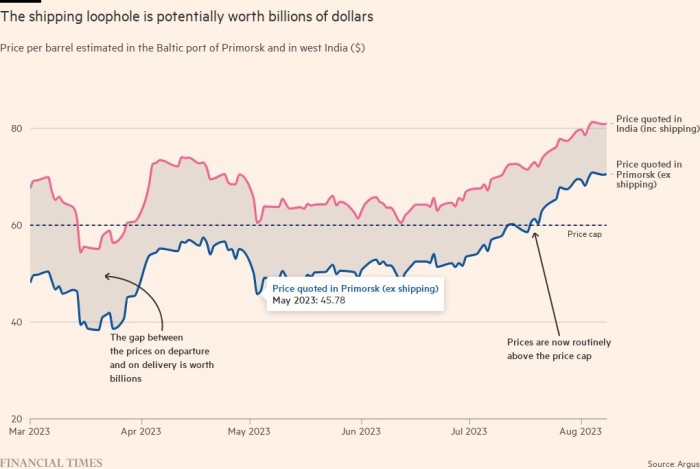

Customs records issued in Russia from December until the end of June indicate that the average price of crude oil shipped to India was around $50 per barrel in Russia’s Baltic ports. This kept the sales in line with the cap, which applies to the so-called “free on board” (FOB) price, or the cost of the oil at the port of loading.

But Indian customs data shows that the prices actually being paid in India after delivery — the so-called “cost, insurance and freight” (CIF) price — over the same period had amounted to $68. This was a marked discount on world oil prices, which averaged around $79 per barrel over the period, but implies an $18 per barrel rise in prices between the Baltic and India.

Figures from Argus, a pricing agency, also point to a large spread. Argus estimates that the average price of Urals crude has been $14.90 per barrel higher in India than in the Baltic since data started to be collected in February. This is in excess of Argus’s estimates of the actual price of shipping, which has averaged around $9 per barrel.

An official at an Indian state-owned oil company which bought some of this oil told the FT that Indian buyers were buying inclusive of shipping costs. The official said that no negotiation was allowed over freight arrangements or costs.

The excess charges are therefore likely to have been captured by the sellers of the oil. According to Kpler, the data analytics company, the oil producers Lukoil and Rosneft have made direct sales to Indian refineries. In other cases, the sale is managed by trading companies that have emerged in the past year with close links to several Russian oil companies.

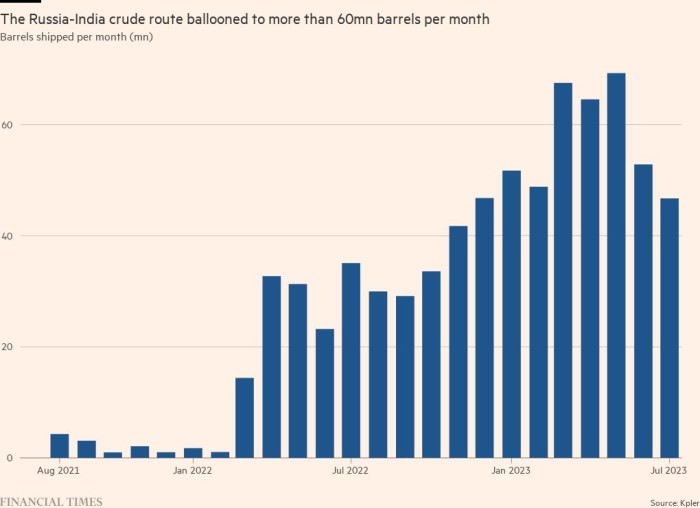

Kpler estimates that Russia shipped 108mn barrels from the Baltic to India from May to July in 134 vessels, a time when the spread between Argus prices averaged $17 per barrel, after taking account of the lag between departure and delivery. At that time, Argus estimates that commercial shipping rates averaged $9 per barrel, suggesting that the overcharging may be worth around $800mn.

Hilgenstock said: “If Russian oil companies and traders agree to these kind of contractual conditions, we have to assume that a portion of the spread is being captured by Russia — whether or not Russia owns the tankers moving the oil.”

Russia does have a hand in the tanker fleet. Of the 134 vessels identified by Kpler as moving Russian oil to India from May to July, the FT has been able to directly link 23 of them to Russian entities via insurance, ownership or management documentation.

Most of these are run by Sun Ship Management, which has been placed under sanctions by the UK and EU for being connected to Sovcomflot, the giant Russian state tanker fleet.

The FT has identified a further 26 “ghost” vessels which were bought by their current owners since the start of the war. Their owners are secret, hidden via shell companies largely in the Marshall Islands and Liberia, but all have dramatically diverted on to the Russian oil routes since being bought — and some have previously been linked to Russia.

In the three months to July, around 40 per cent of the oil shipped from the Baltic was carried by the Russia-connected fleet. The freight cost estimates calculated by Argus imply that this fleet may have earned more than $350mn in revenue on the route over the quarter.

Adding the $800mn by which fees were inflated, this means that Russian entities may have covertly made a billion dollars more in revenue over that period than previously recognised.

India now accounts for around a quarter of Russia’s crude and refined oil exports. Russia’s global oil exports amounted to $39bn in total over these three months, according to the International Energy Agency.

Keeping the price in its Baltic ports below the price cap had allowed Russia to also use ships with western insurance. More than half of the vessels on the route during that quarter were G7-insured, with 46 of them run by Greek ship managers.

The number of western vessels is dropping, however — a consequence of international crude prices rallying 15 per cent in the past month to near $85 a barrel. This has dragged Russian prices higher and closer to the cap. Argus has assessed that average quoted prices in Primorsk, a major Baltic port, rose above $60 last month.

This makes it more difficult for western-linked companies to shift the oil while still obeying the cap. As a result, Greek-domiciled ship managers suddenly started to leave the Russian crude market in July.

The International Energy Agency said on Friday that Russia’s oil export revenues in July reached their highest level since the cap was introduced, even without including inflated freight costs.

The higher prices may also deter buyers, however. An Indian oil official told the FT that the discount was now just $2 to $10 a barrel.

“Indian imports may now decline, as the discounts aren’t as generous,” said Amrita Sen at Energy Aspects. “Their banks are also getting anxious now there are signs that most cargoes are trading above the price cap.”